Louisiana Five leader Anton Lada‘s 1919 setup, complete with Snapper snare drum

Before I start today’s article, an admission. When I was first planning ‘Drums In The Twenties’, one concern was that I didn’t want it to become solely an outlet for thinly-disguised bragging about vintage drum gear – something by which the internet is already well served. Speaking honestly, I don’t really have that much interest in discussing the minutiae of instrument design (no disrespect intended to those who do), and I’d much rather spend my time researching and writing about the music itself and telling the stories of the characters who created it. Furthermore, my lack of interest in discussing old drums ad nauseam is more than matched by a lack of the finances necessary to amass a collection worth boasting about! After starting out playing this style a decade ago, and having sourced just about enough period gear to replicate the most common sounds and styles of the principal 1920s drummers, I’ve been getting on with playing rather than buying more and more just for the sake of it. All the drums in my (very small) collection get used, regularly. I really can’t afford for them not to.

Having said all that, I know many people who are interested in old instruments, and I’ll acknowledge that so far I’ve perhaps been focusing too much on the Heroes and Library sections to the detriment of this portion of the site. Also, I’ve recently been reminded that whilst the subject of antique percussion might seem a dry topic, it’s actually vitally important because it informs the way our Heroes sounded the way they did. I resolve therefore to work a bit harder at writing about the nuts and bolts of the Drums of the Twenties, so that we can better understand those who played them. Today sees the first of two articles examining the evolution of the snare drum – always the drum kit player’s principal instrument – during the 1920s, and hearing and seeing a period example.

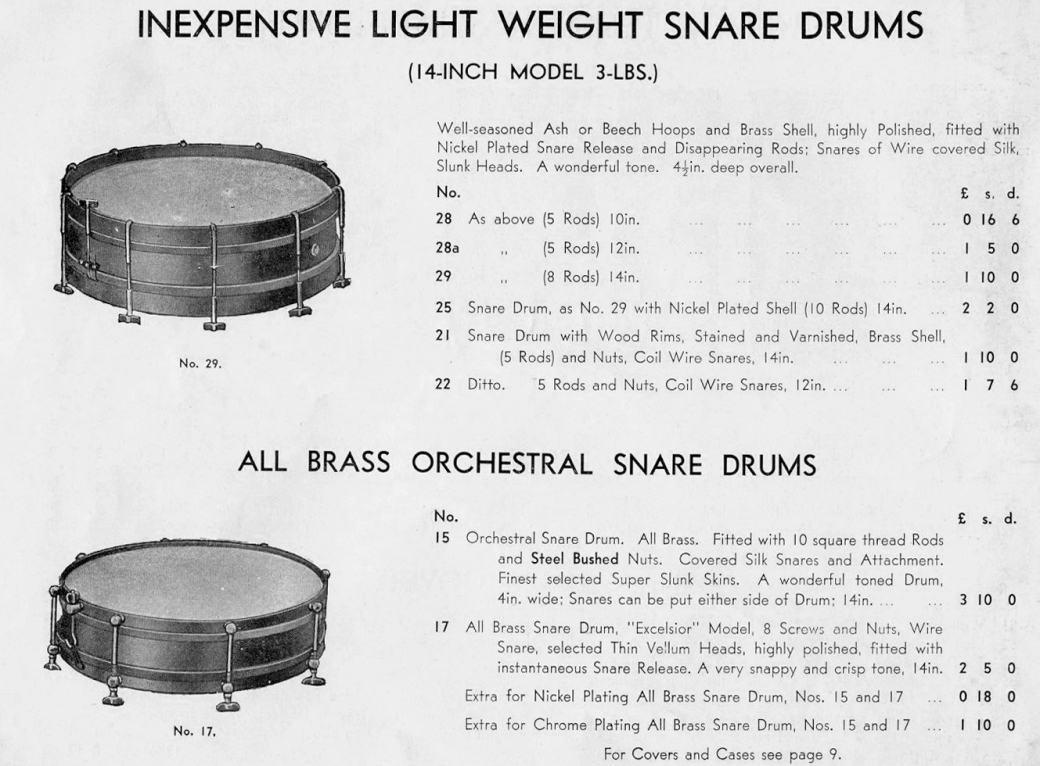

During the early years of the last century, the snare drum was still in the process of evolving from the deep, wooden, rope-tensioned military drums of the 19th century into the shallow, bolt-tuned, usually metal object we know today. Looking at photos from the period and the product catalogues of manufacturers such as Ludwig, Besson or Gretsch, we can see that drummers at the birth of the Jazz Age had a wealth of options available to them when choosing their principal instrument. There seems to have been no ‘standard’ design of snare drum, with examples variously made of steel, brass and various types of wood, in diameters from 10” to around 16” and depths of 3” up to 9” or more. Some forward-looking models incorporated the kind of dual-tension tuning system we’re used to today (i.e. each drumhead could be tuned independently of the other); most, however, stuck to the old single-tension arrangement whereby a turn on a tuning bolt simultaneously tightened both heads towards each other – the merits of which I’ll examine in more detail later). Despite all these bewildering variations, by the late 1910s one particular design of drum became very popular and was still ubiquitous amongst our earlier Heroes: a shallow metal instrument of around 14” to 15” diameter, sometimes marketed as a ‘Tango Drum’ or a ‘Snapper’.

The ‘Snapper’ designation for this drum specification seems to have originated from the British company Hawkes, which was founded way back in 1865. Hawkes began as a sheet-music publisher but soon branched out into making orchestral instruments and spare parts, and by the turn of the century was manufacturing some very high-quality drums at their factory in Edgware, north London, often using imported parts from top American makers. The company would later merge with former rival Boosey & Co. to form Boosey & Hawkes, which at the time of writing is still the world’s foremost publisher of classical music. They no longer make instruments however; the Edgware factory closed in 2001.

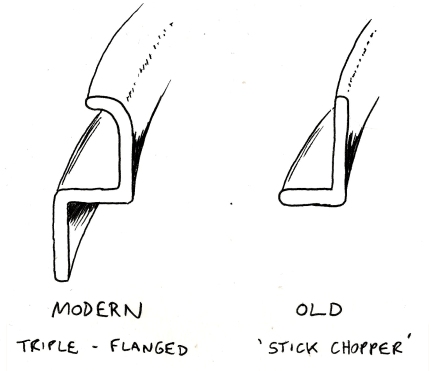

My Snapper (above) is fairly typical of its type: constructed of stainless steel, 3” deep and 14.5” in diameter – good luck fitting that with modern drumheads. There are a few holes where presumably a rectangular maker’s badge was once attached; as yet I can’t determine which badge this would have been. It seems that genuine Snappers made by Hawkes have this stamped into their shells, so presumably mine must have originated from some other company; if anyone can shed any light on this– please get in touch! The counterhoops are typical for the time; deep ‘stick choppers’ – effectively just bent strips of steel sitting directly on the flesh hoops of the heads – rather than the stronger, less destructive triple-flanged type we’re used to today (see diagram below).

Profiles of drum counterhoops seen in cutaway view

These counterhoops are tightened to tension not using a modern square drum key, or even its slot-headed precursor, but with a set of large T-shaped thumbscrews permanently attached to the drum. There has been some conjecture that these drums might have been played ‘upside down’ (i.e. with the snares running across the batter head, in the manner of a Caixa drum in a Brazilian samba group), but this would presumably mean the large thumbscrews facing upwards too, which would be a serious impediment to the player. I’ve also never seen a period photo of a drum set up this way – they uniformly and logically always show the thumbscrews facing down. The snare strainer, meanwhile, is a very primitive affair involving a fish-hook-like bolt tightened with a wingnut. There’s no snare throw lever (why would you ever need to release the snares anyway?) whilst, unlike some of the examples pictured, the tuning bolts are attached to the counterhoops by means of threaded sockets rather than claws. The biggest difference in playing (and gigging with) such an old drum compared to its later descendants arises mainly though the single-tension tuning system. The drawback of this arrangement is obvious: the almost-unlimited range of tuning options available for a modern drum through different combinations of tighter and slacker top and bottom heads at various pitches is completely lost. A Snapper drum is either low-pitched and loose, or (usually) it’s high-pitched and ‘snappy’ – no mixing and matching of those attributes is possible. However, anyone who’s ever tried to use a period drum or banjo on gigs knows that when taken into a dancehall full of perspiring hoofers, natural vellum heads tend to absorb the moisture in the air, making even a well-tuned drum quickly sound like damp cardboard. The redeeming attraction of single-tension tuning is thus that with a few quick twists of the thumbscrews a Snapper can very quickly be brought up to tension again without the need to fiddle around with a drum key. It can even be done mid-song, with the drummer’s free hand.

I’d generally characterize the sound as dry and crisp – the clue’s in the name, after all. With natural vellum heads you do hear more of the drum’s fundamental tone over the snare sound, something common to all snare drums of the period on record as well as in the flesh. Snapper-style drums were used extensively by ragtime drummers during the 1910s, and had their greatest moment of prominence during the ‘Fabulous Fives’ craze inspired by the success of the ODJB, whose drummer Tony Sbarbaro in fact used a deep wooden drum several evolutionary steps further back from the Snapper in the development of the instrument. However, we can see and hear similar examples being played by ‘Jass’ Heroes such as Anton Lada (see top of page), and Benny Peyton and John Lucas (below).

In this video below I’ve attempted to demonstrate some of the sounds of early 20s drumming playing the Snapper with both sticks and brushes, and making some comparisons with a couple of recorded examples.

By the time Chauncey Morehouse played his historic solo on ‘Land Of Cotton Blues’ in 1923, the Fabulous Fives craze had all but dissipated and the old Snapper model was already rapidly falling out of use with jazz drummers in favour of the more advanced dual-tension models pioneered by Ludwig and quickly imitated by other makers. These drums offered a much greater flexibility and range of sounds, and it’s likely that as a cutting-edge East Coast drummer Morehouse was probably already brushing away on something a bit more sophisticated than a Snapper – like the beautiful Barry snare drum we see him cradling in the above photo. We’ll learn all about them in ‘Instruments #5’! However, many of his less-illustrious contemporaries continued to play similar instruments throughout the decade, particularly in Europe where hi-tech American drums were much harder to come by.